Arthur C. Clarke and Evolution in Science Fiction

Rage Against the Machinemind, an introduction to Schelling's psychology of myth and aesthetics, and symmetry breaking

When Stanley Kubrick wanted to set an Arthur C. Clarke book to film, he had in mind not 2001: A Space Odyssey, but Childhood’s End. He had to cancel this plan and change to Space Odyssey because another author had already gotten the rights. Childhood’s End was also on the David Bowie book list as well. Everything Arthur C. Clarke ever wrote largely seemed like an attempt to live back up to Childhood’s End, but it largely seemed like he couldn’t because he had abandoned the ideas behind all the imagery that made it so much more interesting than the other books as well as concise when he said he was “99%” sure that there was nothing to the paranormal so he didn’t even want to write about the topic anymore, yet all his books after that seemed to be much more drawn-out and non-concise versions of the same thing. C. S. Lewis considered the book a great tragedy despite how anti-religious it was, and Kurt Vonnegut joked that it was one of the only true masterpieces of science fiction and the rest were by him.

When I read it some years ago, I still considered myself a child despite having the legal rights to do most adult things, and despite thinking it was a compelling thought experiment with great imagery I had numerous criticisms of it. A couple of days ago I discussed that a lot of the plot of The Symmetry Breakers, though not all of it, was my attempt to correct Childhood’s End. However, a lot more was just criticizing the failure of things like Harry Potter and X-Men to be anything like a Bildungsroman and combining them with Wilhelm Meister’s Apprenticeship/Wandering Years and some Stephen King-esque writing with people with psychic powers since I was making fun of the whole “there are two kinds of people in the world: English professors contemplating adultery, and failed English students contemplating cocaine” mentality of “litfic” that bears no relationship to reality in a world where people are unironically inventing technology based on Star Trek. The alien stuff got added in later once I realized there was enough thematic similarity between all these ideas I could just merge them into one overarching plot and tell a much more coherent story. The reasons why go much deeper than anything I think anyone has really considered on this topic, hence these posts.

When I was discussing the plot of Childhood’s End, it was with someone who said she couldn’t read due to ADHD and liked to find synopses of books on YouTube and I told her, why, just go find an audiobook. Then she said she used to watch all these old science fiction radio shows and she wanted to look for one on YouTube. I told her, good idea, that’s more likely to be accurate to the book than people summarizing and discussing it. Then she watched it and said it was good. Then a couple of days later I watched it myself. While it seemed like very much an adaptation, it at least seemed generally true to the spirit of the book, unlike what I heard happened with the horrible mediocre Syfy show. However, it sort of exacerbated feelings I had of being old that weren’t around when I read the book years ago, even though on a rational level, I know I’m not old, and people who actually are old and even middle-aged look at me like I’m basically a baby, which can even be seen in some of the comments on this very blog. It does, however, spur me to action rather than complacency, and even if that’s not always pleasant it’s hard to see how that can be anything other than a good thing.

When the Apollo 11 Moon Landing took place on July 16, 1969, the BBC broadcasted it to the tune of “Space Oddity” by David Bowie. I was almost going to write an article titled “Why Did We Land on the Moon, Anyway?” because in all honesty, the Moon landing has increasingly come to seem quite pointless to me. I agree with sort of the spirit of exploration, however, it was clearly obvious that nothing was there, and I’m not sure how winning a contest to see who can waste the most resources with the USSR was worth our time when maybe we could’ve done a lot better things with all the time, energy, money, and human lives we spent on that.

I think we absolutely should explore space, since like Friedrich Wilhelm Joseph Schelling I agree that there’s sort of an organic nature to everything and thus there’s more of a difference in degree rather than kind between things, so I expect space to be full of life and all sorts of bizarre things. Heck, we’ve already seen the gigantic cloud of ethyl formate at the center of our galaxy. That’s essentially the ester molecule that gives raspberries and rum their scent and flavor. It’s a quite complex organic molecule that on Earth is mostly produced by living things with DNA. We’ve seen a lot of other similar things out in the cosmos as well, such as perylene molecules coming from nebulae. However, we never saw any of those things on the Moon. We already knew what was on the Moon from sending unmanned probes, and it’s not like we were trying to terraform the Moon and turn it into something like Luna from 40k. Sending people to the Moon just for them to land, plant a flag, and come back seemed like a tremendous waste. Additionally, the fact that the quote most associated with it is “One small step for man, one giant leap for mankind” is also quite telling to me. I don’t think anyone deep down really believes that “mankind” has achievements together, which is really the entire point of this essay.

Was the whole US space program based on the idea that if you go to the Moon, you’ll really find some sort of monolith dropped by an alien race like in Space Odyssey and it’ll help you evolve, and it doesn’t matter who individually evolves because the only identity that mattered to Arthur C. Clarke was the collective identity of the species? This is the most anti-Darwinian thing I have ever heard. One, how did the aliens become evolved to begin with? If they found some other kind of monolith, did other aliens drop it, and just keep dropping it ad infinitum? Two, that’s nothing like how evolution is described in anything scientific ever. Evolution is a natural process, not something bioengineered by aliens who might as well just be a vague and uninteresting “the gods of yore” at that point.

It’s also just extremely uninteresting to view evolution as something that happens due to outside forces toward some definite endpoint at which it stops, rather than an ongoing process that’s on some level always occurring and can lead to a potentially infinite number of results. Most importantly, there’s something, especially in Space Odyssey, but to a lesser extent in Childhood’s End as well, that’s sort of very Columbine shooter-esque in thinking that if you kill other living things, then you become more evolved because survival of the fittest. Darwin did discover that natural selection was one factor in evolution, but even he during his lifetime didn’t think it was the primary factor. Darwin was a Lamarckist who based his theories on the Naturphilosophie of Schelling and Goethe, and he was looking for mechanisms besides natural selection and random mutation up until his death.

eoht.info/page/Goethe on evolution

Did Goethe and Schelling Endorse Species Evolution.pdf (uchicago.edu)

Could Chomsky Be Wrong? | Larval Subjects . (wordpress.com)

larvalsubjects Says:

Robin,

Thanks for the reference. From the biological perspective I’m proposing, anything like a fully blown innate universal structure is going to be deeply problematic as I think this represents a highly mistaken view as to how biological development takes place. Similarly, the idea that such a structure is already encoded in genes will be problematic as well as such an account gives genes an “executive role” that treats them as a causal factor that plays a greater role than all of these other developmental factors. I can’t outline all of these details and why I believe they are relevant in the space of a single blog post. If you’re interested in these issues, take a look at Oyama, Griffiths, and Gray, Cycles of Contingency: Developmental Systems and Evolution.

As I already clarified in previous posts– are you just arriving at this blog? –when I refer to individual differences I am not referring to individuals. As I am sure you are aware, in evolutionary theory individual difference precedes species difference and species are a product of these individual differences, i.e., there are random variations, some of these variations confer an advantage, and as a result the organism in question has a better chance of reproducing and thereby passing these differences on. Darwin is able to dispense with species as understood by prior biology, instead treating them as statistically preponderant regularities within a population produced by these sorts of processes. In my original post I argued that philosophy really has not caught up to this revolution in thought as it still has a tendency to privilege forms, essences, etc., and treating them as differing in kind from individual differences. For example, rather than giving a developmental account of the categories, Kant sees it as necessary to postulate a priori categories in the mind as already fully formed and operative to account for cognition. In this respect, Kantian categories resemble the pre-Darwinistic conception of species as eternal and unchanging essences that differ in kind from individual instances of the species. I cited Fodor’s LOT and Chomsky as variants of this way of thinking.

In my book it is not enough for a theorist to say “x has a genetic foundation” or “x is biological” for them to meet the requirements of this Darwinian revolution in thought. Wherever we get the postulation of universals of this sort, whether in the form of Kantian categories or an LOT or a universal grammar, I find myself suspicious and suspect that we’re before updated versions of the old species. To fully meet the requirements of this differential understanding, two criteria must be met: first it is necessary to give an account of how these generalities are formed (and Fodor and Chomsky can somewhat meet this requirement biological). However, second and more importantly, it is necessary to have a developmental account resonant with what we know about genetics that doesn’t already place form or structure in the genes as pre-existent information, but that is able to show the multiple causal factors– only one of them being genetic –through which final phenotypical outcome is produced. This is where, I think, formalists like Fodor and Chomsky go astray, but that’s a very long story that I’m not prepared to go into here.

larvalsubjects Says:

Rob,

I’ve never suggested that Chomsky isn’t a giant in linguistics, but that doesn’t entail that there aren’t major controversies and debates in the domain of linguistics regarding his claims, nor that there aren’t competing positions. It’s also worthwhile to note that the position I’ve been advancing is not from within linguistics per se, but is premised on developmental biology and neurology. Here the issue is one of basic research orientations or assumptions about the nature of development and the relationship between genes and fully developed properties of an organism, or the assumptions one makes about this relationship (i.e., whether or not information is already encoded in the genes). My hypothesis is that we’re going to discover that the sort of nativism endorsed by folks like Chomsky is going to be discovered to be mistaken as we learn more about these developmental processes, the relationship between genes and fully developed properties, and the nature of brain development. Chomsky, of course, wants to say that UG is genetic, but what is he assuming about the nature of genes here? He’s assuming that genes are blueprints that contain fully formed information encoded within them that simply needs to unfold mechanically when given the proper stimulus. It is this assumption about the nature of genes that allows him to say “yes it’s all genetic but as a linguist I don’t need to look at the actual developmental processes– all those nuts and bolts –because it would just tell me what I already know about the UG.” In other words, genes are treated as a program that simply needs to be executed to get the phenotype that results. But this is a highly questionable understanding of the sort of information contained in genes and how developmental processes actually work.

Allow me to draw an imperfect analogy to illustrate the point. Human beings tend to be between five feet and six feet tall. The biological theorist that works from the assumption that phenotypical information is already encoded in genes– that the rabbit is already in the hat –might work from the premise that there is a gene or a set of genes that contains an algorithm for height already encoded in the genes as pre-existing information that merely needs to unfold when it encounters the proper stimuli. As a result, such a theorist devotes all of her attention to finding those particular genes. Now clearly this theorist isn’t entirely misguided as genes will play a role. But what this misses is the role of diet, environmental conditions like heat or lack thereof, gravity, etc. For example, it’s likely that you or I would be much taller if we were born and developed on Mars, and much shorter if we had the diet of a 18th Century American.

“But Chomsky doesn’t deny that environment plays a role as well!” it will be objected. Yes and no. The manner in which one thinks about these developmental processes is going to play a huge role in the sort of research we do and the sort of findings we arrive at. If we think of environment as only a stimulus that triggers pre-existing genetic information, then we will think we’re warranted in saying there’s something like a UG that is invariant and only triggered by these environmental factors. We won’t think that we need to look at the complex mechanics of these developmental processes because we’ll think they’re only hardware that runs the inexorably unfolding genetic program that already contains all the relevant information. By contrast, if we recognize that these developmental processes are not simply a relationship between an innate “program” and an environmental stimuli, we will be much more likely to be extremely cautious as to what we posit as being universal and fixed and will be much more likely to see something like phenotypical results as emergent regularities involving multiple causal factors such that we can’t really say that the information is already there encoded in a program. By analogy, for example, this research orientation would have a massive impact on how we investigate certain congenital diseases. We would, under this orientation, be much more circumspect about claiming that certain congenital diseases are “genetic” because, while recognizing that these diseases require the presence of “gene or gene network x”, we would recognize that the presence of this gene is only one causal factor among many others and that genes do not already contain all the information encoded in them. For example, perhaps gene x only generates phenotypical characteristic y in the presence of certain steroids in the beef of a person’s diet. The point is that if we don’t already have this sort of research orientation, these complexities are almost entirely invisible to the theorist and we fall into a sort of transcendental illusion where we retroactively project certain results back into the genes, rather than recognizing them as the emergent results of multiple-factors that they are.

Once upon a time I walked into Wal-Mart and, gazing upon its inhabitants the Walmartians, contemplated whether or not I was actually the same species. Then I decided I wanted to write a joke piece about that and I looked up what the actual definition of a species is because the reproduction definition isn’t actually the most accurate one. I then found that we really have no great definition of a species that works for all species, and furthermore, the one that’s applied to humans, the aforementioned reproduction species concept, is actually question-begging and kind of a little absurd. You see, historically, hominins (a more specific category than hominids, which has recently been changed to include other great apes) freely hybridized, and that’s why when you discuss people who are alive today, there’s so much talk about people having certain amounts of Neanderthal and Cro-Magnon and Denasovian DNA.

The statement that all people alive today are the same species because they can interbreed (though there are people who can’t interbreed as well) seems like it’s basically just something that’s assumed in order to stave off the spectre of racism, though obviously asking that question doesn’t make you a racist, since I asked it by joking about People of Wal-Mart, who are generally people from the same ethnic backgrounds as myself. However, if there were more than one species in the genus Homo walking around today by whatever definition, we would have no way to measure it, and that feels a little absurd, though obviously different “races” aren’t different species and even Charles Darwin was very clear about that. If some other, actually important and novel trait, not something shallow and pointless like skin color, started showing up and that led to some kind of speciation event, there would be no way for anyone to say anything about it because, well, it’s Homo, Homo species generally all interbreed quite easily. That sounds like science fiction, so it’s easy to understand why it’s not exactly a priority for people to define, but then, we can’t even decide whether there’s one or four species of giraffes, so figuring it out for the infamous camel-leopards would likely lead to figuring it out for us too without anyone having to consider that to be really out-there. However, it does seem like the cohesion definition of species was also always “the only game in town” since Darwin and before.

Species Concept - an overview | ScienceDirect Topics

How Many Giraffe Species Are There Really? | Blog | Nature | PBS

It’s quite interesting that the view of society we have in general is as “the machine,” and challenging certain aspects of society that are considered problematic is “raging against the machine” like the band, Rage Against the Machine. I think society really is set up as being like a giant machine and we need to, well, evolve past that. The whole obsession with the idea that AI will somehow transcend humanity and possibly become “the Singularity” as people took Voltaire’s quote “if God did not exist, it would be necessary to invent Him” as “that’s a great idea, let’s invent a God since we don’t believe in one” seems like the literal apotheosis of the idea of taking everything as being mechanical. Yes, I can discuss criticisms of Chomsky being wrong due to not taking Darwin’s ideas seriously enough, and also post Rage Against the Machine, because I am done with the culture wars. People can be right about some things and wrong about other things, and anyway, I’m not an anarcho-syndicalist or anything else far-left just because I don’t like that society has turned into a big machine either. If people are uncomfortable with their inability to place my political views, maybe they should read more of what I write, since my whole thing is that I’m very done with the culture wars, and I’m going to quote G. K. Chesterton and Noam Chomsky positively in the same article if I want, and I guarantee you the G. K. Chesterton is coming up in the original article that this one has become a prequel to, about the influence of Schelling’s philosophy on Tolkien. Schelling’s philosophy was deeply and highly influential on Tolkien, but I found it impossible to explain the idea of myth in Schelling and Coleridge without explaining all the ideas of evolution found in the Naturphilosophie, and since I had just watched a radio show version of Childhood’s End due to recommending the book to someone who said she couldn’t read novels due to ADHD, I decided to take this opportunity to explain those concepts here. Yes, this article, which is all about evolution, is a sort of prerequisite to that one, which is all about Christianity and mythology. I’m genuinely convinced Schelling became a sincere and lowercase-o orthodox Christian because of evolution, as much as that might seem contradictory or at least like a complete nonsequitur to most modern ears.

I have absolutely no fear of an actual AI, at least not anything that’s remotely close to what’s being developed now; I only have some concerns about people treating the AI like their golden calf, and acting like it must be capable of things I think it can’t be just because they think it’s logically necessary for AI to be capable of those things and inferring it must be secretly performing them in a way they don’t understand or perceive. I am only concerned some people will go from watching AI hallucinate to essentially hallucinating about AI themselves, and even then, I’m not that concerned, since I myself know better, and so do many other people. However, the fact that society is already organized like a giant machine, in many cases by actual social engineering self-styled psychohistorians, I think is hurting a lot of people. I think the Urphänomen of this kind of incident is the Tavistock Institute and what happened with the detransitioner crisis recently. Look into what other kinds of things they’ve engaged in, and then use the detransitioner crisis as a prototype and you can understand everything else they’ve done throughout history much more easily, which also makes it clear there’s no reason to fear the cult of the machine-god Omnissiah and what have you. This is why I write literary analysis despite it not being my main academic interest: I think it’s an infinitely more insightful form of psychology than all the statistical mechanics of the Tavistock Institute.

Statistical mechanics | Psychology Wiki | Fandom

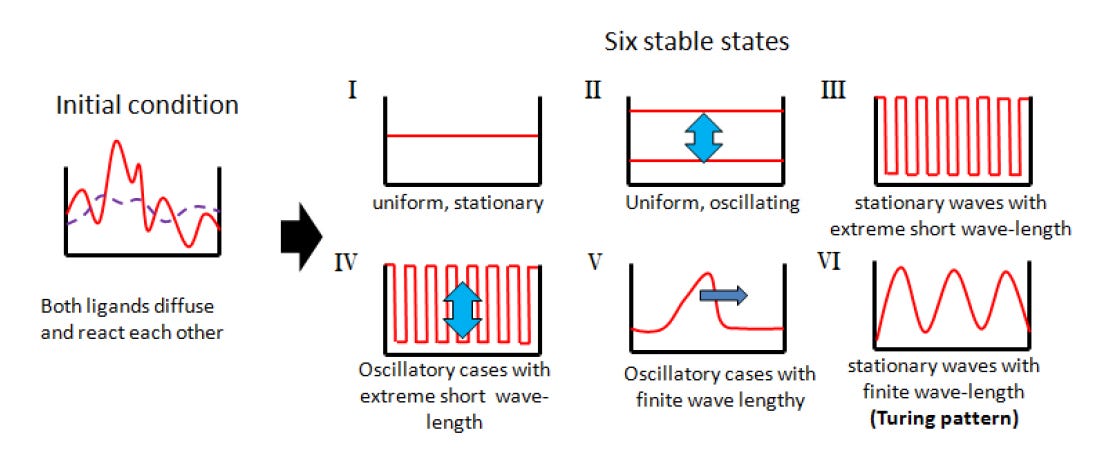

There really does appear to be a sort of non-essentialism in Darwin’s philosophy, and I think adopting that is really the key to helping our civilization peacefully transition instead of collapsing. People must stop identifying with some essentialist conception of “humanity,” the kind of view held by people such as Nick Bostrom and Elon Musk that leads to all the absurdities of longtermism. I know it’s not too interesting for me to talk about my show/book/comic/whatever format that I haven’t written yet, but this is really where the idea of “symmetry breaking” that originally gave the name to The Symmetry Breakers came from. The Symmetry Breakers was the original name, then I changed it to Bluebird for a while because of the linguistics paper “The Blue Bird of Ergativity,” then I learned there’s a relationship between the idea of symmetry breaking and morphogenesis in Turing’s semi-famous model of morphogenesis and decided Symmetry Breakers was better after all, even though I didn’t know about that when I came up with that name.

I had read about the idea of symmetry breaking in one of those pop-sci physics books years ago and I thought it was interesting, and I was considering the idea of what gave a life worth. I didn’t possibly think that the idea of “being human” could give a life worth, since virtually everyone agrees that Hitler’s life doesn’t have worth to use the obvious extreme example, in addition to having long adopted this idea of nonessentialism toward humanity under the influence of David Bowie, Nietzsche, etc. Many people will think most lives have worth and a few people such as Hitler are the exception, but I don’t think that’s true either, because most people did support the Nazis after all, and there’s the whole Sturgeon’s law thing which I think is accurate. In religious terms for people who care about that, it’s generally believed that most people are going to Hell, and someone like C. S. Lewis refuted the idea of universalism while still thinking positively of some universalists such as George MacDonald, he simply had him repent of his universalism in the afterlife.

However, it’s not necessary to get religious at all to think about such a question, because I do think this is essentially the reductio ad absurdum toward longtermism and to a lesser degree, the whole Effective Altruism project from whence it sprang, both of which I think can be subsumed under the idea of pronatalism. Is it really somehow unethical to not fill the Universe with as many human lives as possible since they won’t get to possibly experience anything good? What if those unborn people were mostly a bunch of Hitlers and Nazis? It doesn’t seem reasonable to fill the world with billions, trillions, or more of Hitlers and Nazis. It does seem reasonable to maximize the number of pleasant lives, but I don’t see how that follows from trying to maximize the number of human lives period, much less the longtermist proposition of future beings needing to “share our values.”

Is it really some great moral evil that a rock isn’t a human being, or even conscious? I highly doubt it. Since there’s a reductio ad absurdum against filling the world with as close to infinitely many people as possible, it must be concluded that something other than merely existing entitles one to an overall positive experience. Since merely existing does not entitle someone to a positive experience, it follows that some people, and possibly most or, logically, all people may be essentially condemned, which can easily apply to both the religious sense but also the more secular sense of whether or not people get to have lives that are generally worth living whether or not there’s any kind of afterlife. Then I compared that idea to symmetry breaking, and I decided the symmetry wasn’t broken simply upon being born, but some time after or before that more generally. That led to the idea of The Symmetry Breakers, and that idea persisted even when I played with different names, but since I learned about symmetry breaking in morphogenesis, I decided I had to change my unfashionable story about mutants back to that. And yes, Nick Bostrom is unironically terrified of real-life turning into something from a John Wyndham novel. If he takes his articles where he mentions those ideas off his site out of some kind of sense of embarrassment, I’ll upload it to archive.org on my account Ur Phänomen. Yes, my avatar is the “Biotechnology from the Blue Flower” picture.

The Future of Human Evolution (nickbostrom.com)

What is a Singleton? (nickbostrom.com)

Internet Archive: Digital Library of Free & Borrowable Texts, Movies, Music & Wayback Machine

In physics, symmetry breaking is a phenomenon where a disordered but symmetric state collapses into an ordered, but less symmetric state.[1] This collapse is often one of many possible bifurcations that a particle can take as it approaches a lower energy state. Due to the many possibilities, an observer may assume the result of the collapse to be arbitrary. This phenomenon is fundamental to quantum field theory (QFT), and further, contemporary understandings of physics.[2] Specifically, it plays a central role in the Glashow–Weinberg–Salam model which forms part of the Standard model modelling the electroweak sector.

The Turing pattern is a concept introduced by English mathematician Alan Turing in a 1952 paper titled "The Chemical Basis of Morphogenesis" which describes how patterns in nature, such as stripes and spots, can arise naturally and autonomously from a homogeneous, uniform state.[1][2] The pattern arises due to Turing instability which in turn arises due to the interplay between differential diffusion (i.e., different values of diffusion coefficients) of chemical species and chemical reaction. The instability mechanism is unforeseen because a pure diffusion process would be anticipated to have a stabilizing influence on the system.

The two photons that, as shown in Fig.4, are emitted in symmetrically tilted directions in the FWM process, are in a state of quantum entanglement: they are precisely correlated, for example in energy and momentum. This fact is fundamental for the quantum aspects of optical patterns. For instance, the difference between the intensities of the two symmetrical beams is squeezed, i.e. exhibits fluctuations below the shot noise level;[27] the longitudinal analogue of this phenomenon has been observed experimentally in KFC.[28] In turn, such quantum aspects are basic for the field of quantum imaging.[29][30]

Lugiato–Lefever equation - Wikipedia

I think this ties back into Michael Levin’s idea of morphogenesis having more to do with an electromagnetic basis, but the thing is, the entanglement basis is correct too, it’s not just one or the other. I think that has a parallel to the exact Michael Levin video I showed above: it’s not just mechanical, but it’s also not just organic and entirely non-mechanical, there are both aspects. The electromagnetic aspect is mechanical, but it’s also entangled, and the entangled aspect is the non-mechanical, organic, and “rhizomatic” aspect. However, it isn’t just like random particles in atoms and molecules of living things are what’s entangled, it’s specifically these non-classical electromagnetic interactions. I plan on writing a paper about that once my friend’s friend gets back to telling my friend about how to write papers and then I learn from her, but in the meantime, have more literary analysis. Literary analysis going off into some sort of actual biophysical metaphor is how we do things at Michaela McKuen’s Metaironic Metamodern Metamorphology after all.

Firstly, "they use stroboscopic quantum non-demolition measurements to prepare an entangled atomic spin state at the start of the detection sequence," in order "to reduce the quantum noise coming from the atoms, and improve the sensitivity of the magnetometer beyond the standard quantum limit."

Secondly, during the free evolution period, they utilized a new method enabling them to shift the resonance frequency of the atoms to match the changing frequency of the RF field. This allowed the atoms to build up signal from a single arbitrary RF waveform, while blocking unwanted signals from orthogonal waveforms. As a result, they detected weak RF magnetic-field signals with a 25 percent reduction in experimental noise due to the quantum entanglement of the atoms.

Researchers Use Quantum Entanglement To Detect Radio Waves (rfglobalnet.com)

So, I think Arthur C. Clarke’s connection with the space program and the idea that somehow sending a few people to the Moon has anything to do with the human species as a whole is not at all a coincidence. I read today that Childhood’s End was actually supposed to be an allegory for the British Empire and what happened when the former colonies broke free. This both makes little sense given the internal logic of the story, and also adds a negative subtext to quite a lot of it. In the original novel, it’s quite clear that the Overlords were subverting evolution through some kind of artificial genetic engineering and turning the next stage of humanity into something that would otherwise never have happened. Humans were going to just continue to evolve into a psychic species which interacted with the material world, not be sucked into “the Overmind,” which came off to me a lot like the Black Mirror episode San Junipero, where people were preserved after death by having their consciousnesses uploaded to a computer to be zonked-out and not influence anything real for the duration of the physical universe as we know it, but more psychedelic.

Unlike many “randos” on the Internet, I never got the sense that the Overmind was some kind of predatory or parasitic entity like the C’tan or Chaos from Warhammer 40k that wanted to absorb souls, I got the sense it was actually entirely engineered by the Overlords themselves to contain species they thought were dangerous, and that made me really disagree with the message of the book despite the fact I thought it was interesting and recommended it to people on the basis it was interesting just so they could have something to think about. In the context that the Overlords are actually the British Empire, then genetically engineering all the children “for your species’s own good” seems quite a bit like the stories of sending of Amerindians and others to these boarding schools to force them to conform. While I think there were positive aspects to the British Empire and colonialism, that certainly wasn’t.

However, the explanation that it’s supposed to be some sort of allegory for colonialism makes it make a lot more sense why Arthur C. Clarke somehow didn’t find it abysmally depressing, since he wasn’t even really considering it on the more speculative or fantastical level most readers were. This is just in my opinion one of many instances of an allegorical approach to fiction being something that’s not satisfactory, which is incidentally what Tolkien was all about and something Goethe wrote a little about long before then. That should tie this article nicely into the one I was working on but put on hold about Tolkien and Schelling, which was getting too complicated without having some sort of introduction to the ideas of the Naturphilosophie and how that relates to the idea of myth as the basis of psychology. This article hasn’t gone too into that but I do think discussing the idea of nonessentialism in Darwin and how Arthur C. Clarke seems to have a really poor grasp on evolution is a good segue into that.

I think what the British Empire really did wrong, and it did do things wrong even if I also think it did things right, was rely too heavily on this idea of the machine. For all that historical societies were, often falsely, considered to be too authoritarian (democracy is an old idea and even many medieval societies actually held votes for their monarchs or otherwise picked them based on non-hereditary standards such as just warlords,) I can’t see the idea of society being “the machine” as being remotely applicable to most of them. In Childhood’s End, the Overlords are very clearly presented as being essentially these beings who are purely bound to the physical plane without any kind of psychic or “spiritual” aspect at all, which is where I think the C’tan comparison really comes in, but many people say that that’s the vision of the future they would want for humanity, not “transcendence” into the Overmind. The parallel of humanity evolving into a psychic species and that being interrupted by outside forces in Warhammer 40k does show a lot more parallels to Childhood’s End than to even John Wyndham despite all the “HERESY!” meming, though to be fair, neither of these are books you hear about much at all in the context of inspirations behind 40k. Childhood’s End seems more well-known than anything by John Wyndham in general, but even that isn’t well-known at all, people just talk about A Canticle for Leibowitz and Frank Herbert’s Dune all the time.

I do think John Wyndham ironically has a pretty good grasp on the whole Darwinian nonessentialist concept of evolution despite all the out-there ideas in his novels with telepathy and postapocalyptic worlds and what have you, and the juxtaposition of those two is what really what rubs modern audiences the wrong way, which I will get back to in my other postponed essay on “The Reenchantment of Fiction.” So in many ways I have to view John Wyndham as being far superior to Arthur C. Clarke. John Wyndham is better by most sort of “conventional literary” standards as well, it’s just largely considered completely unrealistic by the modern standards of science fiction, though that makes me kind of wonder how Kurt Vonnegut apparently didn’t even consider him when stating that Childhood’s End was one of the only masterpieces in science fiction and the rest were by himself.

I think if we want to preserve civilization against the forces that are destroying it and causing people of all sorts of cultural, political, and religious or irreligious persuasions to wax apocalyptic, we must really abandon the Machinemind. The Machinemind is the mentality of everything being a machine. In some ways ideas like the Borg from Star Trek and later the Phyrexians from Magic: the Gathering are really the extension of the idea of the collective mind in Childhood’s End, but they subvert it by clearly painting it as a bad thing. The Overmind from Childhood’s End doesn’t superficially look mechanical in any way since it only appears as a pattern of light in the sky that made me imagine those “Eye of God” nebulas that are sometimes found in space, but when I read the book, I did very clearly interpret it as being something completely artificially engineered anyway. The world will have to change to survive in any form, but that’s just what life is, anyway, and that’s something that you can directly find in Darwin, and Goethe.

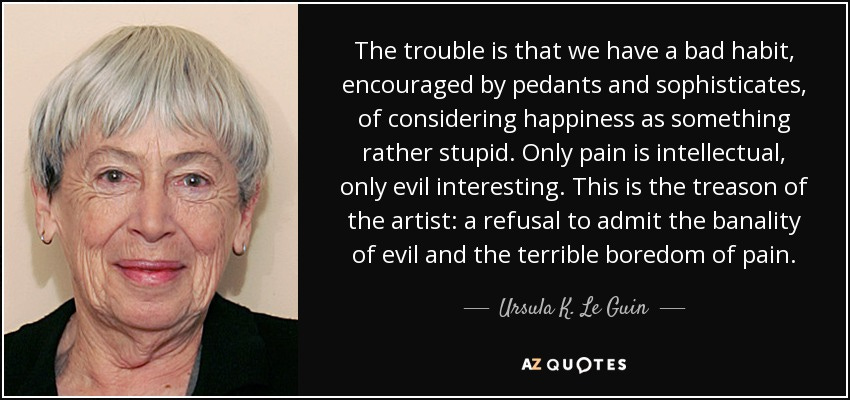

Aside from the necessity for us not to care so much about machines in our day-to-day lives or as a focus of our economic activity, and not to turn AI into some golden calf when I think it’s obvious AI in any form that’s being discussed now will never be able to do what people fear it could do or hope for it to do, we must get rid of the all-encompassing machine in our own mind that makes us into automata in a way. We must stop thinking about everything as a machine like we have a hammer and everything is a nail, and we must certainly stop treating society as a machine. And back when I wrote complaints about how awful Jack Kirby was, well, why was he so bad anyway? The Celestials fail as being these cosmic horror entities because they’re machine-gods. There’s no evolution of the Celestials and no evolution on any of the Marvel Eternals or DC New Gods worlds because they’re all mechanical, and that’s dreadfully boring, though easy to accept for people accustomed to thinking of the Universe as a great machine. They assemble new ones inside planets like they are mining resources to build robots, and they blow up the planets they are mined from rather a lot like the ending to Childhood’s End. Likewise, we can’t have the X-Men, they keep trying to replace them with Avengers, Inhumans, and all these other things that might be perfectly interesting if they weren’t trying to forcibly get rid of their most popular franchise, because we can’t have anything organic in machine-land. They have to retcon mutants to being something bioengineered by Celestials, which is as anti-Darwinian and biologically essentialist as it gets, and I get the sense that that really repels most people on an instinctual gut level, and not only people like me who know about these topics on the level of explicit knowledge. Likewise, all these stories about the Eternals and New Gods end with them all dying. They’re not Kantian, they’re Hegelian. Hegel was the opposite of Schelling while he was alive and the two of them had a rivalry, but Kant took a lot of feedback and updated his ideas when he communicated with Fichte and Schelling. Hegel, on the other hand, simply tried to say he superceded Schelling as a result of his dialectic, though this clearly makes Schelling et al. and not Hegel and the Hegelian cult the true continuation of Kant’s thought. Hegel had the absolute worst conception of aesthetics ever, a combination of pure kitsch and a sensuous focus with the idea that tragedy and suffering were the only things intellectually simulating.

Hegel’s Aesthetics (Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy)

Art, for Hegel, also gives expression to spirit’s understanding of itself. It differs from philosophy and religion, however, by expressing spirit’s self-understanding not in pure concepts, or in the images of faith, but in and through objects that have been specifically made for this purpose by human beings. Such objects—conjured out of stone, wood, color, sound or words—render the freedom of spirit visible or audible to an audience. In Hegel’s view, this sensuous expression of free spirit constitutes beauty. The purpose of art, for Hegel, is thus the creation of beautiful objects in which the true character of freedom is given sensuous expression.

The principal aim of art is not, therefore, to imitate nature, to decorate our surroundings, to prompt us to engage in moral or political action, or to shock us out of our complacency. It is to allow us to contemplate and enjoy created images of our own spiritual freedom—images that are beautiful precisely because they give expression to our freedom. Art’s purpose, in other words, is to enable us to bring to mind the truth about ourselves, and so to become aware of who we truly are. Art is there not just for art’s sake, but for beauty’s sake, that is, for the sake of a distinctively sensuous form of human self-expression and self-understanding.

…

Beauty, however, is not just a matter of form; it is also a matter of content. This is one of Hegel’s most controversial ideas, and is one that sets him at odds with those modern artists and art-theorists who insist that art can embrace any content we like and, indeed, can dispense with content altogether. As we have seen, the content that Hegel claims is central and indispensable to genuine beauty (and therefore genuine art) is the freedom and richness of spirit. To put it another way, that content is the Idea, or absolute reason, as self-knowing spirit. Since the Idea is pictured in religion as “God,” the content of truly beautiful art is in one respect the divine. Yet, as we have seen above, Hegel argues that the Idea (or “God”) comes to consciousness of itself only in and through finite human beings. The content of beautiful art must thus be the divine in human form or the divine within humanity itself (as well as purely human freedom).

Hegel recognizes that art can portray animals, plants and inorganic nature, but he sees it as art’s principal task to present divine and human freedom. In both cases, the focus of attention is on the human figure in particular. This is because, in Hegel’s view, the most appropriate sensuous incarnation of reason and the clearest visible expression of spirit is the human form. Colors and sounds by themselves can certainly communicate a mood, but only the human form actually embodies spirit and reason. Truly beautiful art thus shows us sculpted, painted or poetic images of Greek gods or of Jesus Christ—that is, the divine in human form—or it shows us images of free human life itself.

…

The third fundamental form of romantic art depicts the formal freedom and independence of character. Such freedom is not associated with any ethical principles or (at least not principally) with the formal virtues just mentioned, but consists simply in the “firmness” (Festigkeit) of character (Aesthetics, 1: 577; PKÄ, 145–6). This is freedom in its modern, secular form. It is displayed most magnificently, Hegel believes, by characters, such as Richard III, Othello and Macbeth, in the plays of Shakespeare. Note that what interests us about such individuals is not any moral purpose (which they invariably lack anyway), but simply the energy and self-determination (and often ruthlessness) that they exhibit. Such characters must have an internal richness (revealed through imagination and language) and not just be one-dimensional, but their main appeal is their formal freedom to commit themselves to a course of action, even at the cost of their own lives. These characters do not constitute moral or political ideals, but they are the appropriate objects of modern, romantic art whose task is to depict freedom even in its most secular and amoral forms.

Hegel also sees romantic beauty in more inwardly sensitive characters, such as Shakespeare’s Juliet. After meeting Romeo, Hegel remarks, Juliet suddenly opens up with love like a rosebud, full of childlike naivety. Her beauty thus lies in being the embodiment of love. Hamlet is a somewhat similar character: far from being simply weak (as Goethe thought), Hamlet, in Hegel’s view, displays the inner beauty of a profoundly noble soul (Aesthetics, 1: 583; PKÄ, 147–8).

Last but not least, I do see the Machinemind being thoroughly expressed through the Hegelian dialectic, which is another thing you can observe in Childhood’s End. The Overlords present a binary choice: humanity destroys itself as well as wreaking destruction beyond itself by becoming a “telepathic cancer,” or it gets artificially subsumed into the Overmind by the Overlords’ genetic engineering of the children. (Also, “Telepathic Cancer” sounds like a great title for an Anaal Nathrakh song, or for anyone who wants it first if Anaal Nathrakh doesn’t get there in time.) This seems like a false dilemma, and is very reminiscent of the idea of the Hegelian dialectic, especially as conceived of by people engaged in conspiracy theories (and while there are many outlandish and schizophrenic conspiracy theories, there are also known true ones like MK-ULTRA, so this is not meant in a derogatory sense.) I will return to this aspect in “The Schellingian Tolkien,” but I think this is sort of the response to the Hegelian dialect: creativity. If you don’t want to be crushed between the two sides of the machine like the trash compactor in Star Wars, you must pick some way out, and possibly have to create it yourself.

This is Coleridge’s idea of “Imagination and Fancy,” which is also the basis of Tolkien’s idea of primary and secondary creation or subcreation, since Tolkien was quite into Coleridge, who was explicitly heavily influenced by Schelling. When I say I really think Schelling just became an actual Christian due to evolution, as little sense as that might initially make to many people, this is exactly what I mean, and if you want to see sort of the flip side of that idea, check out articles on

such as Of Ham and AiG (which I contributed to even though it wasn’t the first article he ever wrote on that topic by a long shot.) Tolkien even drew a picture called “Xanadu,” based on Coleridge’s poem “Kubla Khan,” and hung it above his mantle. Xanadu is also what was referenced in Citizen Kane by Orson Welles as well. Considering all the other things Tolkien was influenced by and the fact C. S. Lewis heaped praise upon Childhood’s End, perhaps Tolkien’s idea of the Gift of Men being to transcend beyond the spheres of Arda was based on the ascension of the children in Childhood’s End. Aragorn might be 210 years old when he dies, but I’m sure the elves who notoriously were “there 3,000 years ago” think he’s basically a child, and the Hobbits, considered a sub-race of Men rather than their own independent race like Elves, Dwarves, or Valar, certainly are reminiscent of children with their stature and behaviors.So, I hope this has been a good setup to other things I’ve been trying to work up toward, but found were too complex to start with. Since I think people really do process stories more than rote facts, I hope these analyses of stories can help people understand important concepts more, and I can build up slowly. Feel free to join in too, mutants and norms! (We all know mutants and norms are the two real genders.) The more analysis the better! Most of us are just writers here and not professional literary analysts or critics, and I think we’re all in a long tradition of non-professional people including Emerson and Goethe when we do this. When we who are not professional literary analysts or critics do this kind of writing, we are certainly raging against the Machinemind, not that there’s anything wrong with being professional either. Even professional “polymathy” is discouraged by the Machinemind, so simply, branch out, evolve, stay soft, and don’t break.

![It is not the strongest of the species that survive, nor the most intelligent, but the one most responsive to change." Charles Darwin [886x612] : r/QuotesPorn It is not the strongest of the species that survive, nor the most intelligent, but the one most responsive to change." Charles Darwin [886x612] : r/QuotesPorn](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!li_y!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Fc7532bad-108d-4478-af1b-80f379d3ba1a_886x612.png)

great article. very in depth.

I am trying to evolve Sci Fi.

wit A.i

https://open.substack.com/pub/saxxon/p/back-to-the-future-4-sci-fai?r=1u8tu3&utm_campaign=post&utm_medium=web